Berger never explicitly notes the connections between these images, leaving their relationship open-ended.Ĭhapter 3 helps elucidate the relationships between the previous essay's images of women.

Throughout the essay, women appear in paintings and photographs, across an apparently diverse range of settings and times: photos of contemporary women at work, oil paintings of women in the nude, and advertisements of women selling products are all reproduced side-by-side in this essay.

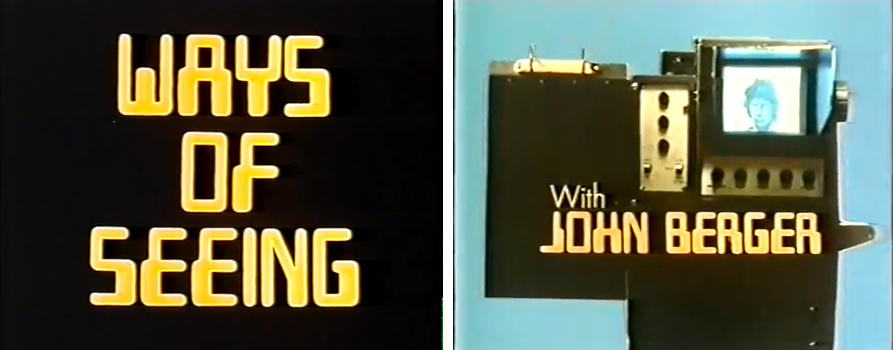

They share a common subject matter: women. The second essay in the book is all in images-text appears only sporadically to attribute paintings, and not all the images are attributed. This is the core tenet of the first essay: reproduction changes what images mean by circulating them in new ways and alongside new ideas, breaking down the rarified narratives handed down from the elite that often seek to stabilize our understanding of their meanings. Drawing on Benjamin, Berger argues that reproductions impact images by bringing them into new contexts, opening up new (and often, more democratic) possibilities for their interpretation. Throughout the first essay in the book, Berger draws heavily on the work of Walter Benjamin to explain how reproduction is one possible way to change the meaning of images. From this premise, Berger explains how images have layers of deeper meaning beyond what they show on the surface: they can offer a valuable document of how their creator saw the world, but their underlying politics can also be obscured or mystified in order to uphold the powers that be. Another way of phrasing this: all images are encoded with ideology, regardless of whether their creators consciously want them to be. This term is used to describe paintings, photographs, films, or any other representation that humans can construct, and it is assumed that every image externalizes its creator's way of seeing. One way that people can recreate their way of perceiving the world is through images. John Berger opens his seminal Ways of Seeingwith an observation that seems counterintuitive, considering its status as a written text: that, as we inhabit the world, we constantly perceive it, only later naming the things we see, making language insufficient for conveying the way we see the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)